Exhuming Jonah, and The Myth of Redemptive Violence

Preface

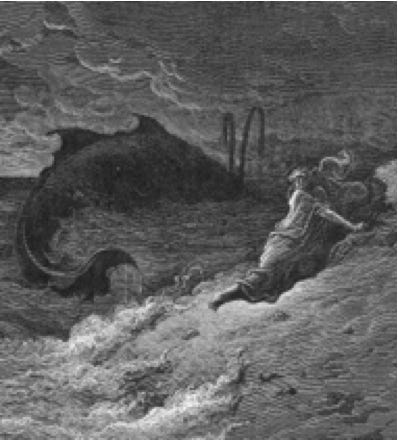

Every Sunday School student learns the fantastic story of Jonah and the Whale. The miraculous regurgitation of the reluctant prophet after three days in the leviathan’s belly is a whopping tale as big as any fish tale ever told. The rest of the brief story of this minor prophet from the Jewish scriptures is hardly as dramatic. Jonah learns his lesson not to refuse his Lord’s bidding, and the rather generic warning message of repentance delivered to the citizens of the ancient city of Ninevah. [Note: Now abandoned, Ninevah was the oldest and most populous city of the ancient Assyrian Empire, situated on the east bank of the Tigris opposite the modern-day city we know all too well, Mosul, Iraq.] There is only a passing reference in Jonah’s prophetic message, with regard to Ninevah’s great offense; and the wicked ways from which they must mend their ways to avoid total annihilation.

When the news reached the king of Nineveh, he rose from his throne, removed his robe, covered himself with sackcloth, and sat in ashes. Then he had a proclamation made in Nineveh: “By the decree of the king and his nobles … all shall turn from their evil ways and from the violence that is in their hands. Who knows? God may relent and change his mind; he may turn from his fierce anger, so that we do not perish.” When God saw what they did, how they turned from their evil ways, God changed his mind about the calamity that he had said he would bring upon them; and he did not do it. Jonah 3:6,8-10

If one finds the mythic tale of Jonah and the whale too much to swallow, more incredible perhaps is what the people of Ninevah managed to pull off. If only we could find a way to do something similar just about anywhere around the world these days.

Commentary

On the world stage these days, there are almost too many moving parts to keep track of all the players and deadly games people play. A snapshot of one day’s recent headlines ran like this: International investigators cancelled plans to visit the crash site of the Malaysian airliner shot down by Russian separatists armed with shoulder-fired missiles; after receiving reports of escalated armed conflict in the area. Despite a proposed extension of a temporary ceasefire, Hamas is still firing rockets into Israel, prompting still more retaliatory strikes. Israel claims the right to defend itself by maiming and killing countless civilians in their efforts to annihilate their enemy. Syrian refugees still flood neighboring countries, as the Assad regime continues to gain the upper hand in that country’s relentless civil strife. All the while President Obama, meeting with leaders from El Salvador, Guatamala, and Honduras, pledged the vast majority of illegal migrant children lacking “humanitarian claims” (hence not technically “refugees” seeking asylum) will be sent back to those countries wracked by violence. But of all the hotspots flooding the news and erupting in so many corners of our global village, one headline in particular caught my attention this last week from Mosul, Iraq. “Historic Tomb of Jonah Destroyed by Isis Militants.” A photograph showed the explosion and subsequent rubble of a Sunni Mosque which was alleged to be the burial site of the Prophet Younis, the Arabic name for Jonah. Though ISIS claims to adhere to the Sunni branch of Islam, they have nonetheless blown up or bulldozed any Sunni shrine they deem "un-Islamic." Go figure. Well, that’s more than a little ironic, I thought to myself. God regurgitated Jonah from an early grave, only to have some fervent believers go and blow up his purported final resting place. What, once upon a time, God apparently could not do – or was not willing to do – was not a problem for some of God’s children hell-bent on advancing some twisted ideological agenda through means of violent force.

What, once upon a time, God apparently could not do – or was not willing to do – was not a problem for some of God’s children hell-bent on advancing some twisted ideological agenda through means of violent force.

In the New Testament synoptic tradition, Jonah is mentioned in both Matthew and Luke’s gospels. As a precursor to Jesus, Jonah too spends three days in a temporary tomb. And like Jonah, the Jesus character depicted in the gospels will fulfill his prophetic role, warning people to repent of their wicked ways with sackcloth and ashes for a symbolic period of forty days. The difference, of course is that where that legendary city of Ninevah took heed, changed their ways and was spared, for those to whom Jesus directed his message up to this very day, it seems to have fallen on deaf ears. The other interesting thing about Jonah -- whose name means “dove” (the biblical symbols of of peace and future promise) -- is that we never know the rest of his story. What happens between the time he gets spit out of the belly of “the great fish” and delivers his redemptive message to Ninevah; and his ultimate death and burial? Like Lazarus sprung from an untimely tomb and unbound by Jesus’ liberating voice to do who-knows-what until his ultimate earthly demise, the Book of Jonah provides us with only a brief sequel to his own deliverance from the fish’s belly, and the message he subsequently delivers to Ninevah. Once the king of Ninevah heeds the call of repentance and the whole lot is saved, Jonah expresses anger and resentment over what he suspected all along. Namely, the Lord’s boundless mercy would prevail in the end. But the question of what Jonah, Jesus you or I might do -- once we have been spared or raised up to a place of greater awareness -- may be found in Jonah’s ancient message. His warning to turn from wicked ways was pretty generic and not very specific, except for the half-line about turning away from “the violence that is in their hands.” It is, in fact, that age-old reminder of our self-defeating reliance on the so-called myth of redemptive violence. Somehow, we continue to believe every desperate situation can be resolved and redeemed by violent means. More than the mythic tale of Jonah and the whale, it is the myth of redemptive violence that is still alive and flourishing everywhere we turn. And it’s no wonder. Without question, it is far preferred to the non-violent alternative requiring compassion, concession, and self-dispossession. As the late Walter Wink once observed (The Power That Be), “The myth of redemptive violence “is the simplest, laziest, most exciting, uncomplicated, irrational, and primitive depiction of evil the world has ever known.” It appears the earthly remains of Jonah can be exhumed with bombs and bullets, but his message remains securely dead and buried.

© 2014 by John William Bennison, Rel.D. All rights reserved.

This article should only be used or reproduced with proper credit.

To read more commentaries by John Bennison from the perspective of a Christian progressive go to