Bedrock Christianity and Bedrock Americana

A Precarious Reflection for the Thanksgiving Holiday, 2012

Preface

The presidential election is history, and you’d like to think we ought to be able to move on and enjoy the holidays; followed by that creeping encroachment of the traditional mass consumer spending spree, to the delight of retailers. But the debate over one of the most contentious issues remains unresolved; namely, the federal deficit / budget crisis, the battle over new revenues (taxes) and a looming “fiscal cliff.” The day after the election, the Speaker of the House of Representatives delivered a speech, meant to re-establish his political party’s position on such matters. In his remarks, he alluded to scripture, perhaps with whatever seal of approval that might provide: “In the New Testament, a parable is told of two men,” he reflected. “One built his house on sand; the other built his house on rock. The foundation of our country's economy – the rock of our economy – has always been small businesses in the private sector.” Not to put too fine a point on it, but the “rock” to which that little scriptural illustration was referring was Jesus’ ethical teachings; based on an unconventional and (as it turned out) unpopular form of radical egalitarianism. The use of an analogy for the two types of foundations for anyone who would undertake to construct their life was well known and used in the ancient Near East. But the New Testament employs it specifically to conclude that section commonly known as the Sermon on the Mount (in Matthew 7) or Sermon on the Plain (in Luke 6). And, that particular “rock” had little to do with keeping one’s fiscal house in order, taxes to Caesar, the entrepreneurial spirit, or the free enterprise system. That bedrock of Jesus’ teaching did however have implications as to how we might order our lives in society; in closer alignment with what those scriptures depict as something more akin to what the divine had in mind. As well as how we ought to treat one another, without vacuous pretence or self-embellishment. The last Words and Ways commentary explored how we might reconcile our very human motivations of gratitude, generosity, sufficiency, abundance and excessive concern for self. As a Thanksgiving holiday reflection that customarily takes stock of our bounty and abundance, this commentary explores what is clearly the precariousness of our lives, in light of the bedrock of what we call our Christian faith.

The Precariousness of All Things, and the Impermanence of God

“Rock of Ages cleft for me

Let me hide myself in thee.”

Hymnist Augustus Montague Toplady, 1763

Legend has it that Rev. Augustus Montague Toplady, an itinerant English preacher, was inspired to write the old Christian hymn of personal salvation, when he was caught in a nasty storm and sought refuge in a rocky crag in the Mendip Hills of England. It wasn’t the first, nor last, time mortals sought a form of divine protection and favor for refuge and repose that was touted to be as sure and firm a foundation as rock. That’s what religion is often purported to promise; something – indeed, sometimes anything -- of permanence to which one can cling; when the ground beneath our feet begins to shift, and the old reliable pillars we’ve constructed can no longer support the weight of the pressures brought to bear upon them. This could certainly include those outmoded human institutions and belief structures (religious, social, political, economic, etc) that bear little resemblance to present-day realities. In a “religious” context, when all else fails, the prophets and soothsayers call us to turn (or return) from what is retrospectively regarded as our wayward ways in exchange for another covenant, or “grand bargain.” When we do so, we want to believe if there remains at least one constant, amidst the uncertainties of life. God – or, at least our notions of who, or what, God is -- should be that one certain anchor and rock. After all, isn’t that how we typically try to define the divine, as all-knowing, all-powerful, all-everything we want “Him” to be? The seeming contradiction we find in our own biblical tradition, however, is a kind of divine dynamic contradiction, when it comes to making our images and imaginings of God as one who is inanimate, unchanging and permanent. And it becomes clearly problematic when we seek to construct some sort of bedrock of faith. For example, Moses strikes what one might call the rock of improbability at Horeb, and from it flows living water (Numbers 20:1-13). Jesus is depicted in his triumphal, but short-lived, entry into Jerusalem with the proclamation that if the shouts of “Hosanna!” were suppressed, then irrepressible stones would begin to sing (Luke 19:40). But if among those things that would be constant include improbability and irrepressibility, there’s certainly the human desire nonetheless to try to nail down something unchangeable and irrevocable when it comes to God. We need look no further than Matthew’s gospel, and the early community of believer’s desire to define its own organizational lines of ecclesiastical authority. Conveniently the words put in Jesus’ mouth not only ascribe to Petros (the Rock) the keys to the kingdom, but all earthly authority to speak as proxy for the absentee Galilean sage, as well. It sure sounds like a rock solid case for permanent divine sanction. Of course it’s also certainly an inconvenient truth to recall only a few verses later in Matthew’s same gospel the same Rock is referred to as Satan, because Peter’s ideas run along the lines of human thinking, and not God’s ideas (Mt. 16:23). From the get-go it appears the early church struggled to hold fast to the heart of Jesus’ message Then there’s Peter’s thrice-repeated denial that he has no idea who Jesus is when accused of being a collaborator (Mt. 26:69-73); which turned out to be more telling than even Peter knew. And finally, there is Peter’s full conversion of faith in a gospel message of radical self-sacrifice that comes closer to what would constitute the original bedrock of Jesus’ teaching. But if it is at all troubling that God is truly then a dynamic, living a reality, that can (and does) change, we might keep in mind the bedrock of Jesus’ teaching comes from an itinerant preacher who modeled a way of life reflective of a different way of seeing the world; not of unchanging permanence, but receptive and responsive to the dynamic relationship with such a God of change. Where then might we look to find any fundamental and eternal message? It may have been the same question Augustus Montague Toplady asked when he found himself in just as precipitous a predicament as one we face today. Today the children of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob are engaged in armed conflict among themselves in Israel and Gaza, we find ourselves just days away from going over a national fiscal cliff, and Thanksgiving for many has been reduced to counting our greatest blessing as being the fact that we’re not as bad as a lot of other folks. There seems nothing but sand beneath our feet where you’d think there should be rock.

Bedrock Christianity

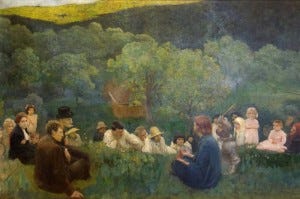

Sermon on the Mountain - Karol Ferenczy, 1896 The pastoral scene of gentle folk lounging on a rolling hillside suggests a message far removed from the precipitous and precarious depictions of life.

I once knew a man who built his whole life on sand,

The sand of I and me, and me and I, and mine.

And when the winds of life and living

came and swept around his heart,

It went out like a candle in the night.

I knew another man, no wait, I think that it was woman,

Gently built her life and limb on you and yours,

The winds all tried to take her,

spin her ‘round and then forsake her,

She was rock though, and she stood to love again.

The Wind Song, Singer-Songwriter Joe Wise

The compilation of miscellaneous teachings, sayings and illustrations that comprise what we call Jesus’ “Sermon on the Mount” (or “Plain” in Luke 6) could be considered the bedrock of the gospel message. It contains much of what is generally considered to be as close as we can come in the gospel narratives to what was likely at the heart of Jesus’ teachings. Even so, editorial license and retrospective additions by the gospel writer’s early faith community are clearly evident.

That is not necessarily to say it is what subsequently came to be the predominant expression of cultural Christianity in the Western world. That’s why it’s helpful and important to try as best we can to go back to the original source, as near as we possibly can. As one of my old professors recently put it succinctly,

“If Christians declare that Jesus was the “anointed one,” (the “Christ”) it is only by redefining the role of the “anointed one” to fit what Jesus actually said and did. To be authentically Christian is to be Christo-centric. That can take many forms, and Christians can argue passionately as to whether the center is the life and teaching of Jesus, the apostolic witness to Jesus, the cross as effecting atonement, the resurrection as demonstrating a unique relation to God, or incarnation as presenting God to us in and through a human being.”

John Cobb, Christian Faith Watered Down, 2011

The many interpretations of Christianity which Cobb enumerates result in many different kinds of Christians, of course; despite the monolithic way in which popular media and culture like to caricature those who would still call themselves Christian. It is the life and teaching of Jesus – as best we can discern it, and still persuasively apply it in contemporary terms – that remains for me that living, dynamic relationship with all that I would still regard as a present reality of what I would still call God. So it is that this collection of Jesus sayings in Matthew begins with those strange and paradoxical “blessings,” commonly called the Beatitudes; congratulatory exclamations for those unfortunate and fool-hearty types for whom the world as it seems would regard as anything but blessed. (Mt. 5:1-11).

[Luke’s comparable “Sermon on the Plain” (Luke 6) contains the additional “but woe to you who …” material, that has an eerie contemporary ring to it. Interestingly, such “woes” could aptly describe the precarious predicaments we face today.]

Even within those three chapters in Matthew, the fragments of what many scholars consider authentic words of the historical Jesus form only the basis for subsequent elaboration by the gospel writers. If we want to attempt to clarify all that by reducing and simplifying what Jesus probably actually said, it might well be reduced to a pretty simple list. If honest about it, most preachers will confess they have one sermon they preach over and over. The way the message is conveyed changes, but the message remains the same. Like other preachers, Jesus expressed his single vision of God’s reign and domain in many ways: in parables, drawing from the wisdom literature of his own religious tradition, etc. One Biblical commentator reduces those variations to seven simple sayings of Jesus:

- Turn the other cheek

- Walk the second mile

- Give up your shirt as well a your coat

- Forgive seventy times seven

- Love your neighbor

- Love your enemy

- Do to others as you would have done to yourself

Harry T. Cook, The Seven Sayings of Jesus

I briefly pick three sections from this composite collection (Sermon on the Mount) that – in the most original form we have received it – is still a revised, retrospective version of what may have once constituted the original words and intentions of the Galilean rabbi’s message. First there are the “blessed are …” beatitudes. Next there is this: Jesus taught, “A city sitting on top of a mountain can’t be concealed. Nor do people light a lamp and put it under a bushel basket but on a lamp stand, where it sheds light for everyone in the house.” Matthew’s community preceded the saying with, “ You are the light of the world.” And then added their own applicable commissioning, “That’s how your light is to shine in the presence of others, so they can see your good deeds and acclaim your Father in the heavens.” They took Jesus’ words, interpreted them, and applied them. They might have been the earliest of those to do so, but would certainly not be the last. The important point was how they understood (or misunderstood) and appropriated (or misappropriated) his words. This is caution is reiterated several times through this section in Matthew in words Matthew’s community retrospectively attribute to Jesus, for example: “Beware of false prophets, who come to you in sheep’s clothing but inwardly are ravenous wolves.” (Mt.7:15) And “Not everyone who says to me, “Lord, Lord”, will enter the kingdom of heaven, but only one who does the will of my Father in heaven.” (Mt.7:21) Then the entire section concludes with this illustration,

“Everyone who pays attention to these words of mine and acts on them will be like a shrewd builder who erected a house on bedrock. Later the rain fell, the torrents came, and the winds blew and pounded that house, yet it did not collapse, since its foundation rested on bedrock. Everyone who listens to these words of mine and doesn’t act on them will be like a careless builder, who erected his house on sand. When the rain fell, and the torrents came, and the winds blew and pounded that house, it collapsed. It’s collapse was colossal.” And, when Jesus had finished this discourse, the crowds were astonished at his teaching, since he had been teaching them on his own authority, unlike their (own) scholars. [Matthew 7:24-29]

The story of the two houses built on two different foundations was part of the common folklore at the time of Jesus, and was certainly not original to him. Only the specific application of the tale by the early followers of the Galilean sage is of importance here. The teachable moment centers on the meaning of all of Jesus’ core teachings that have preceded this conclusion to this. The impression purportedly made on the crowd of listeners – that is, “astonishment” – was added emphasis by the gospel writer, clearly meant to subvert the authority of the religious, as well as political, establishments. To take these three excerpts from this collection, then, there is within those congratulatory “beatitudes” a core message that could shine as a beacon and everlasting light; as well as a vision of what Jesus repeatedly described in so many different ways as the nature of God’s intended and still hoped-for “domain;” that it might still be laid as a sure foundation, and the means by which we might build a more abundant life. So what? I thought of all this – about those beatitudes, about the light on a hill illuminating them, and about solid foundation for those who’d use such “beatitudes” as the building blocks that might withstand the inevitable winds that continually shake the rafters of our national psyche and global community. I thought about it in terms of how we, as a society, may have built for ourselves an economic house of cards that teeters on the brink of collapse. I thought about it in terms of how fellow heirs of our Abrahamic faith tradition stand on the brink of an escalation of violence, with the continued delusion that any permanent peace can be achieved by means of retaliatory-armed conflict. And I thought about what constitutes for me my understanding of a bedrock Christian faith as we turn our observance to this quintessential American holiday; a holiday that is still difficult to think of exclusively in terms of turkey, football and the onslaught of a creeping Black Friday, without taking a moment to reflect in some sort of religious way. For as we remain a nation imbued with overflowing abundance, it seems fitting to take a moment to reflect about who we are, and all that we have; as an inescapable part of this national observance.

Bedrock Americana

We come on the ship they call the Mayflower.

We come on the ship that sailed the moon.

We come in the age’s most uncertain hour,

And sing an American tune.

But it’s alright, it’s all right,

You can’t be forever blessed.

America Tune, Singer/songwriter Paul Simon, 1973

British comic Eddie Izzard once quipped this wonderful one-liner about the pilgrim’s story: “They set off from Plymouth, and landed in Plymouth! How lucky is that?” But as we all learned in grade school, the rock upon which the pilgrims landed and subsequently named Plymouth turned out to be a mixed blessing. The first Thanksgiving was anything but bucolic, and our pastures of plenty have seen both good times and bad ever since. Thanksgiving is a national holiday observed in many faith communities in this country, where traditional hymns are typically sung; gratefully acknowledging the Lord’s blessing for an abundant harvest. This year, despite record drought that devastated crops, followed by ravaging floods that washed away entire seaside communities, most folks will still find ways to feast and fortify themselves for the holidays yet to come. Local customs being what they are, some of us may also still tune in to a local radio station somewhere for the annual observance of listening to all 18 minutes of Arlo Guthrie signing “Alice’s Restaurant.” But an unlikely Thanksgiving hymn that’s always been a favorite of mine was written and recorded by the song-poet Paul Simon almost forty years ago. While the melody was a blatant rip-off of one of J.S. Bach’s moving hymns more than two centuries before (commonly known as “O Sacred Head Sore Wounded”), American Tune is a beautiful, haunting rendition of the American story during our most challenging times that call for serious introspection; from the “First Thanksgiving” to the one we celebrate this year.

Many's the time I've been mistaken,

And many times confused

And I've often felt forsaken,

And certainly misused …

I don't know a soul who's not been battered

Don't have a friend who feels at ease

Don't know a dream that's not been shattered

Or driven to it's knees …

But it's all right, all right,

We've lived so well so long

Still, when I think of the road we're traveling on,

I wonder what went wrong,

I can't help it, I wonder what went wrong.

And I dreamed I was flying.

And far above, my eyes could clearly see

The Statue of Liberty, drifting away to sea

And I dreamed I was flying. …

And we worry and fret over giving up a little of all we have so we don’t throw ourselves – and everyone else – over a fiscal cliff? Jesus illustrates his many teachings with examples of wealth and treasure. Earthy possessions rust and get stolen, and accumulating more than you need is foolishness. A humble spirit and modest offerings that represent a significant portion of one’s modest means is more pleasing to God.

But if the bedrock of Jesus’ teachings could be reduced to a few sayings, it might be those beatitudes that seem to turn the conventional ways of this world on its head; and suggest a different kind of precarious path as we make our way through this world. Instead, those few sayings from Jesus might be condensed further to a one-liner about faith and hope, once uttered by the modern-day prophet Martin Luther King; that “unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word in reality.” In 1630, the Puritan preacher Jonathan Winthrop preached a sermon entitled, “A Model of Christian Charity.” He envisioned the Massachusetts Bay Colony (and what was, in fact, the birthing of our nation) would one day be an example of a “city on a hill.” The phrase would become part of the lexicon of our political rhetoric, of course; most notably by what is now regarded almost nostalgically by many as the “Reagan era.” Indeed, in his farewell address in January 1989, Ronald Reagan repeated the phrase one last time, with the elaboration,

“...I've spoken of the shining city all my political life, but I don't know if I ever quite communicated what I saw when I said it. But in my mind it was a tall proud city built on rocks stronger than oceans, wind-swept, God-blessed, and teeming with people of all kinds living in harmony and peace, a city with free ports that hummed with commerce and creativity, and if there had to be city walls, the walls had doors and the doors were open to anyone with the will and the heart to get here. That's how I saw it and see it still... “

It’s helpful to remember that before Reagan appropriated the line it was used by a Puritan preacher; who himself drew upon an image recorded in Matthew’s gospel; and in the context of Jesus’ central teachings that were to form the foundation upon which the bedrock of that gospel message was intended to be built. The winds would always surely come and beat upon the house. And, if politicians (and preachers) would consider not only the source, but the original meaning and intention of the source from which they would appropriate their quotes, perhaps our house pitched so precariously would not fall, because it would be built on a rock of another sort.

© 2012 by John William Bennison, Rel.D. All rights reserved.

This article should only be used or reproduced with proper credit.

To read more Words & Ways commentaries, click on the Archives menu at http://wordsnways.com